[Spoilers, CW: sexual assault, rape]

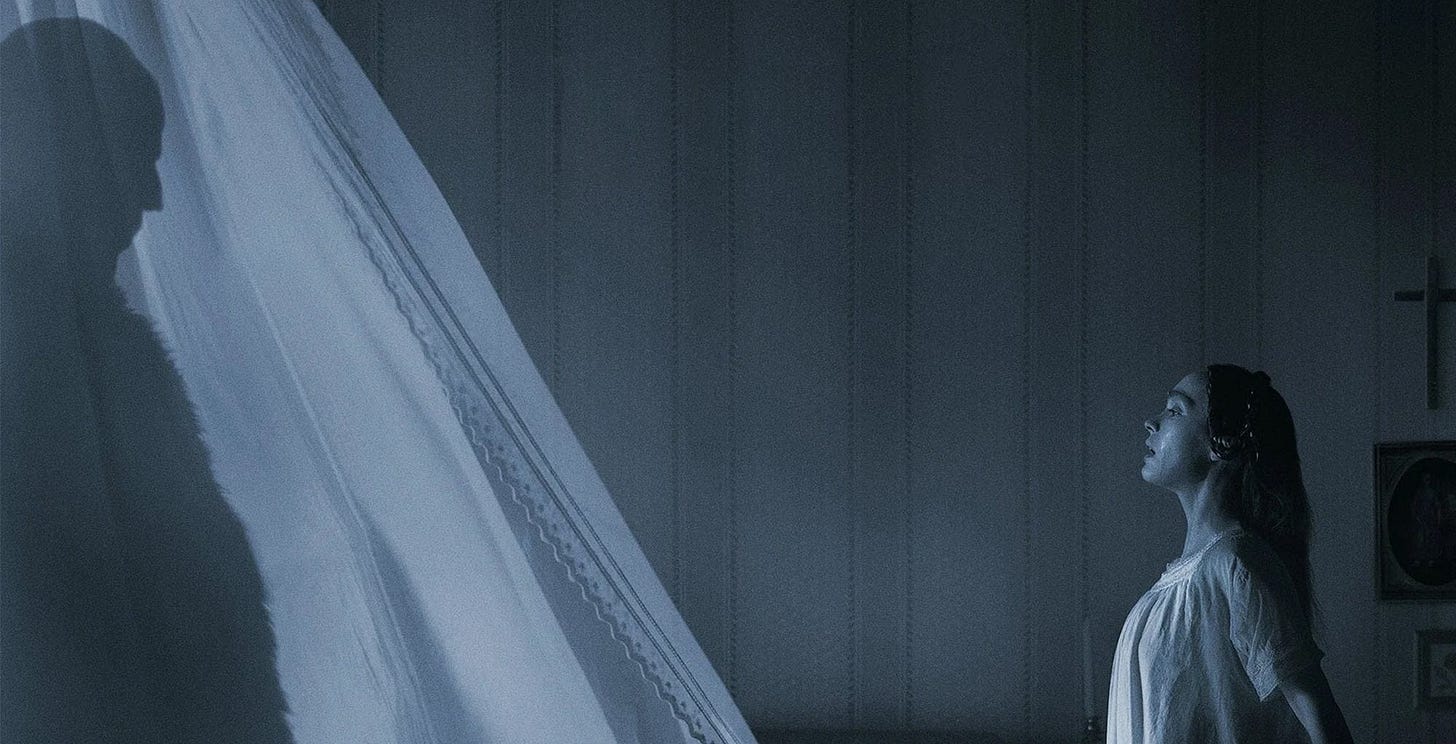

I don’t like horror movies and I’m not really into vampires. I have seen the 1922 Nosferatu, which is a gem of a film—it’s expressive and eerie in a way that modernity cannot completely undo. I planned to give Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu the same wide berth I give all horror movies (and many more besides). But after watching the trailer, I was drawn in. I could say it was Lily-Rose Depp’s cheekbones, or the suffusion of gorgeous, foreboding blue-black shadows that cloak the movie, or the haunted-girlhood creepy music box tune, that finally swayed me. But reader, let me be honest—while these were all compelling factors, it was the flood of “you must bounce on it” memes and one too many subsequently spat-out drinks that really pushed me to give this movie a chance, and thank goodness I did. I love the Eggers retelling for its lush atmosphere and feminist undertones. Yeah, I said that—let’s get into it.

Ellen Hutter (LRD) is now the main character, and it’s through her pain, madness, and torment that we experience the world of 1830s Germany, one in which Ellen is repressed and ridiculed for her ability to communicate with the supernatural. The mounting dread of this dreamlike movie is more suspenseful and doom-filled than scary—something that has made a lot of (predominantly male-identifying) reviewers upset. (I don’t think it makes for a bad horror movie in any way, though again, I’m not a scary movie fan, and am disloyal to and disinterested in the concept of “genre” at all.)

On Reddit, plenty of users are disgusted with the 2024 Ellen. “Ellen just seemed evil and like a liar with no empathy for others,” writes one user. Another notes, “This [movie] is such an allegory to modern girls who ruin their perfect relationships for toxic ones and good caring husbands who are left to their shame and huge therapy bills.” A final contributor adds: “Felt like this movie was just the director letting everyone know he has a cuck fetish.” But like, it’s Reddit, so who cares. Still, I kept seeing a stream of internet content wherein women profess and/or joke about their love for Bill Skarsgård’s Count Orlok, with men foaming at the mouth in the comment sections.

I wanted to see what the pros thought, so I took it upon myself to read an exhausting number of Nosferatu reviews. I was disappointed and a little peeved at many of them, which seem to miss what I consider to be the movie’s great achievement: an honest, suspenseful, morally conflicted take on being attracted to a person of great evil.

Here are three broad categories I’ve identified among reviews, with a few supporting examples. Just for fun, I’ve added the presumed gender of the reviewer as well:

1. Ellen is a victim of sexual abuse/rape; Orlok is a monster:

b. M. “Eggers’ Ellen is…an isolated victim of an abusive supernatural relationship.”

2. Ellen is an active sexual participant:

3. Actually, Ellen’s sexuality is irrelevant to the story:

b. M. “Nosferatu does not deserve the pre-release labels of “horny” that it has been eagerly assigned.”

4. BONUS: This movie isn’t scary at all!

a. M. (obviously.) ~“I never got scared. I couldn’t feel myself immersed in the story! Lily-Rose Depp looks like her dad. 5/10.”

It’s not to say that these takes are wrong or bad, only that I believe the actual message of the movie is much more complicated. Ellen is sometimes crying and scared, sometimes raving and convulsing, sometimes outspoken and calm. She presents as a complex human being. Reducing her to victim or heroine does as much of a disservice to her character as it does to women in real life to whom we give these labels. (And don’t get me started on how these simplistic tropes run the risk of playing into the virgin-whore dichotomy.)

For instance: it’s not obvious if the opening scene is literally a memory, or a nightmare based on a memory. This distinction isn’t just me splitting hairs—understanding the intersection of real-world desire and fantasy is a key cornerstone in making sense of historically under-researched women’s sexuality. Take the example of the rape fantasy, a symptom of contemporary patriarchy and rape culture, where a person finds the concept of being forced into sex arousing. It does not mean that this person wants to be raped in real life. It is precisely the distinction between reality and fantasy that separates actual from imagined violence. But the rape fantasy inhabits a troubling space in the public imagination, where it perches upsettingly close to the phenomenon of victim-blaming, and it’s difficult to grapple with the topic without including a host of disclaimers.

Related is the phenomenon of arousal nonconcordance, where the body responds to a physical signal very differently than the brain does. A common example of this is when survivors of sexual assault become physically aroused despite the obvious violence of their experience. “The very nature of trauma is that it is a complex thing,” notes Lucy Harbron in Far Out. “After being attacked when [Ellen] was just a girl, Orlok’s violence and darkness seemed to shape [Ellen’s] concept of love and sex.”

Nosferatu plays with these ideas without descending into pulpy movie rapiness, instead content to raise ugly, difficult questions about human sexuality through the nuances of the Ellen-Thomas-Orlok love triangle. Ellen both desires Orlok and is terrified of him; her entire life has been shaped by him and she’s deeply ashamed of it. This is both a simple and complicated reality that movie reviewers, in advocating for either Ellen’s victimhood or sexual agency, miss, and in doing so, help to perpetuate a reality where there is no room for confusing, upsetting, trauma-informed conversations about desire. Characters like Ellen are painful to watch, because if she is to be believed, it means that we all have the capacity to crave violent self-negation, and to love it. That might be the scariest thing of all.